I want to preface this post with an acknowledgement—I’m not going to use the term “disability” because I think it implies that a person CANNOT do something; whereas, “differently-abled” alludes to the fact that accomplishing a goal is not impossible. It just may look a little different or take a little longer to achieve.

Physical activity, defined as any bodily movement produced by skeletal muscles that requires energy expenditure, benefits every aspect of health and in daily life can be categorized into occupational, sports, conditioning, household, or other activities, including exercise, which is planned, structured, and repetitive and has as a final or an intermediate objective the improvement or maintenance of physical fitness (1). That’s a fancy way of saying, regularly finding ways to move and challenge your body causes it to change and adapt to the stresses you place on it. Not doing so results in a plethora of negative effects to the body.

Physical inactivity has been identified as the fourth leading risk factor for global mortality causing an estimated 3.2 million deaths globally or 6% of deaths. Globally, 23 percent of adults 18+ and 80 percent of adolescents are insufficiently active, and this number is higher among individuals with a disability. Current evidence goes even further to suggest that inactivity has negative effects on everyone–but the effects appear to be worse for differently-abled people, particularly for those with a traumatic brain or spinal injury. (2)

So…why? Let’s look at some of the barriers preventing this from happening, try to get a better understanding of the benefits of creating healthy physical activity habits, and finally, get some guidance on where to start.

Barriers to Exercise for Differently-abled Adults

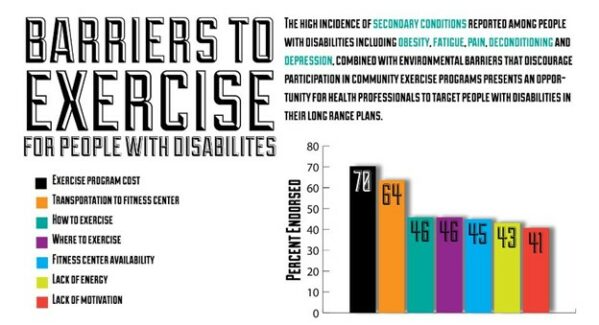

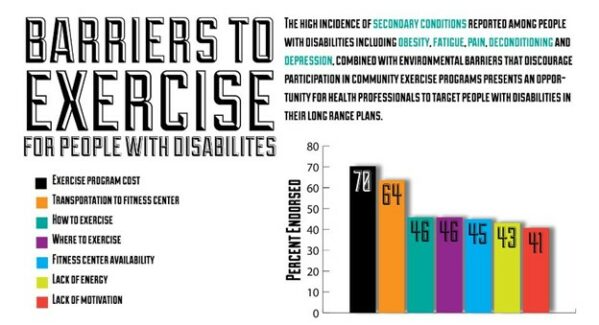

To begin, let’s acknowledge that there are things that prevent differently-abled adults from participating in physical activity. Specifically, those barriers can come from within ourselves (interpersonal or psychosocial), how the body is physically operating (ability), and from the outside world (environmental accessibility).

Let’s deal with the internal first. What’s interesting about this category is that really applies to anyone, regardless of ability level:

- Lack of motivation

- Self-conscious

- Time

- Interest

- Energy

- Knowledge (what to do, how to do it, where to go)

For anyone that’s had an acquired injury to their brain (or spinal cord), the following barriers can pose more issues due to the body’s physical ability (or lack thereof). If you’ve had one of these types of injuries, you may be dealing with any of the following changes:

- Decrease in mobility

- Weakness or paralysis

- Poor balance

- Pain

- Fatigue/low endurance

Finally, the need to use durable medical equipment like a walker or a wheelchair may create barriers from the outside world (2):

- Lack of support system

- Poor integration into the community

- Lack of Counselling by a Physician on role of Physical Activity

- Lack of Adapted Physical Activity Opportunities

- Lack of Accessible Facilities e.g., limited adaptive equipment or space between equipment, no ramps or elevators, poor signage

- Poor Trainer / Coach / Therapist Knowledge Awareness of Traumatic Brain/Spinal injury

- Barriers in Outdoor Areas

- Lack of Transportation

- Cost of the Program

Benefits of Exercise for Differently-Abled Adults

You may be reading all those barriers and just nodding your head. And you probably, in some way, know that more physical activity typically means you feel better. You’re right. We have good evidence that your physical and mental well-being as well as your individual and social development are all impacted by your level of activity. Consider the following examples:

Physical well-being

- Prevention of secondary medical conditions (diabetes, obesity, heart disease, etc.)

- Maintenance of current medical conditions

- Improvements or maintenance of physical strength/balance/endurance

- Make daily tasks easier and promotes independence

Mental well-being

- Improved self-esteem

- Improved cognitive function

- Source of enjoyment/happiness

Individual development

- Development of soft skills

- Impact on employment opportunities/employability

- Improved confidence

Social/Community development

- Reduce isolation

- Create opportunities to bring people together from diverse backgrounds

- Promoting social engagement and trust of others

Exercise Program Guidance

An adaptive fitness program for an individual with a traumatic brain or spinal cord injury should be tailored to address the person’s specific needs and abilities while also considering the impact of the injury on tone and spasticity, range of motion and flexibility, cardiovascular and muscular endurance, strength, and cognitive impairments. Incorporating physical activity to improve these concerns can increase quality of life and ability to perform activities of daily living skills.

Physical Therapists can play a large role in developing physical activity programs, during the rehabilitation phase of treatment and following discharge into the community. Physical Therapists can also play a huge role in educating physical activity providers on the needs of individuals with a traumatic brain or spinal cord injury on accessing community based physical activity programs.

More specifically, aim for 150 minutes per week of moderate-intensity cardiovascular activity or 75 minutes a week of vigorous-intensity cardiovascular activity, or a comparable combination of moderate and vigorous intensity cardiovascular activity, in episodes of at least 10 minutes, spread throughout the week (4).

Furthermore, aim for 2 Sessions per week of Strength Training activity of moderate or high intensity that involve all major muscle groups with 1 – 2 sets of 8 – 12 repetitions. If possible, combine balance exercise with strength 2 times per week (5, 6).

You may be thinking “Yeah, that’s great information, but it still seems a little overwhelming. The barriers are stopping me from experiencing the benefits.” That’s a reasonable point.

Here’s the best advice I can give to—plan and prepare to make a change. Commit to the change TODAY and do it. And then do it again tomorrow. And the day after that. And then again, and again, and again. Literally take it one day at a time. Anything beyond that can be very overwhelming. This is habit formation 101.

Start small and gradually grow it into the recommendations highlighted above. Find ways in your everyday lives to take one more step, one more push, maybe one more time standing throughout your day. If you need help, connect with an expert (ahem, unselfish plug!).

Now, get active!

References

- Caspersen CJ, Powell KE, Christenson GM. Physical activity, exercise, and physical fitness: definitions and distinctions for health-related research. Public health reports. 1985 Mar;100(2):126.

- Physio-pedia. Physical Activity Guidelines for Traumatic Brain Injury. Available from: https://www.physio-pedia.com/Physical_Activity_Guidelines_for_Traumatic_Brain_Injury#cite_ref-1, [last accessed 06/28/21]

- Institute, UK Chief Medical Officers’ Physical Activity Guidelines, 7 September 2019, Available from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/832868/uk-chief-medical-officers-physical-activity-guidelines.pdf, [last accessed 06/28/21]

- US Dept of Health and Human Services. 2008 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans. Available from https://health.gov/paguidelines/2008/pdf/paguide.pdf[Last accessed 06/28/21]

- Irwin K, Ede A, Buddhadev H, Driver S, Ronai P. Physical activity and traumatic brain injury. Strength & Conditioning Journal. 2011 Aug 1;33(4):43-7.

- Martin Ginis, K. A., van der Scheer, J. W., Latimer-Cheung, A. E., Barrow, A., Bourne, C., Carruthers, P., … Goosey-Tolfrey, V. L. (2018). Evidence-based scientific exercise guidelines for adults with spinal cord injury: an update and a new guideline. Spinal Cord, 56(4), 308–321